Communism and Hunger: The Ukrainian, Chinese, Kazakh, and Soviet Famines in Comparative Perspective

Scholars from Canada, France, Italy, Hong Kong, England, Japan, Ukraine, and the United States gathered in Toronto on September 26–27 to examine and compare the Ukrainian, Kazakh, Chinese, and Soviet famines at the conference Communism and Hunger, organized by HREC. The conference explored the similarities and differences between these political famines.

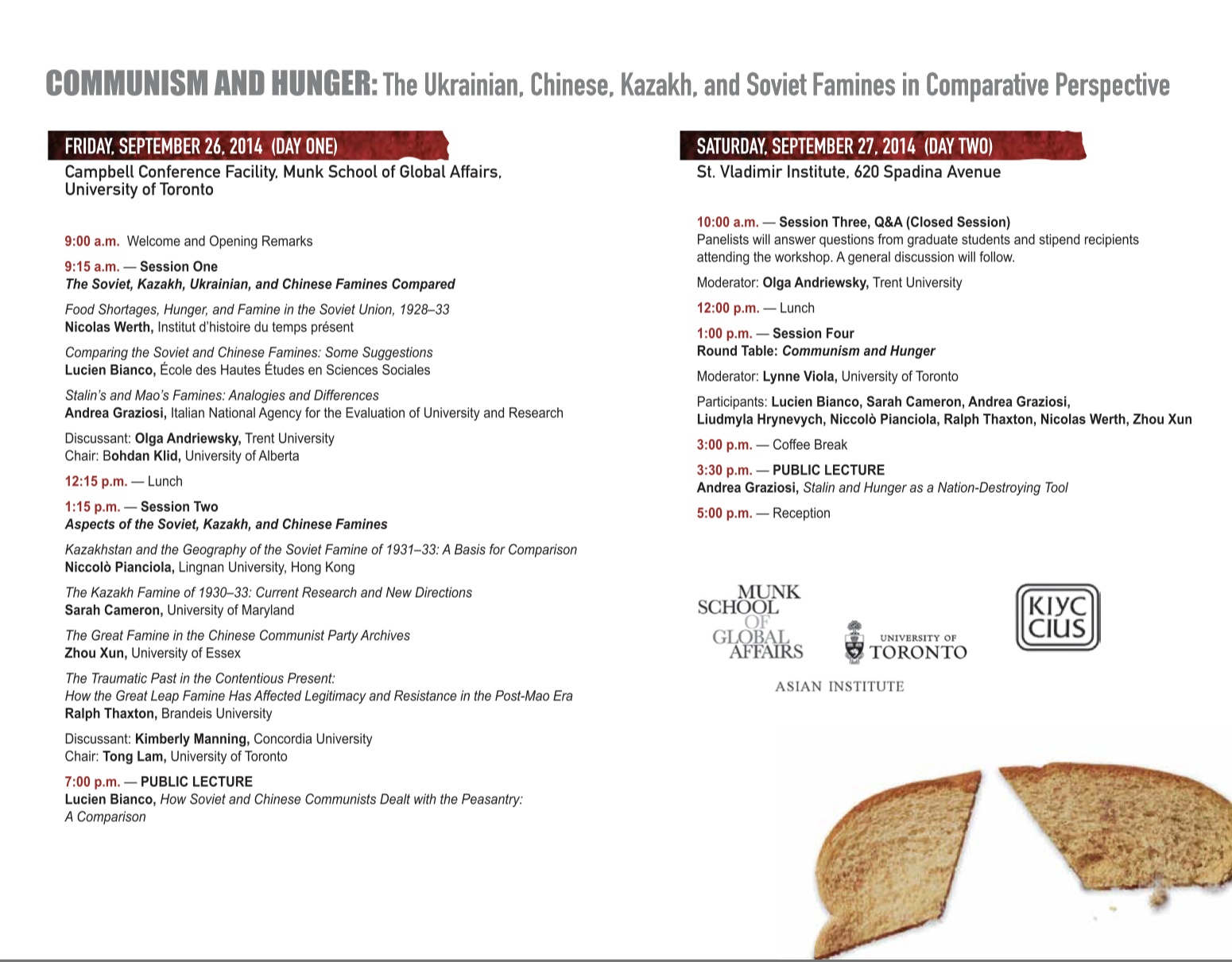

Day One of the well-attended conference, held at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, began with the panel “The Soviet, Kazakh, Ukrainian, and Chinese Famines Compared” and featured Nicolas Werth (Institut d’Histoire du Temps Présent, Paris); Lucien Bianco (l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris), and Andrea Graziosi (Italian National Agency for the Evaluation of University Research, Naples). Olga Andriewsky (Trent University) served as discussant.

The second panel, entitled “Aspects of the Soviet, Kazakh, and Chinese Famines,” featured presentations by Niccolò Pianciola (Lingnan University, Hong Kong); Sarah Cameron (University of Maryland); Zhou Xun (University of Essex), and Ralph Thaxton (Brandeis University, Boston). Kimberley Manning of Concordia University was the discussant. On Friday evening, Lucien Bianco, an eminent Sinologist, gave a public lecture entitled “How Soviet and Chinese Communists Dealt with the Peasantry: A Comparison” before a full house at the Munk School.

The second day, at St. Vladimir Institute, concluded with a round table featuring all of differences between the famines. The scholars discussed how Stalin and the central Soviet authorities were antagonistically disposed to the peasantry, particularly in Ukraine, where uprisings against the Bolsheviks had occurred in 1919 and the peasantry was clearly linked to the nationality question. Consequently, Stalin proceeded with measures to destroy Ukrainian peasant resistance, using famine as a tool. In China the leadership, much of which came from the countryside, viewed the peasantry more positively. Nevertheless, it also unleashed an assault on the rural population with catastrophic results. The political impact of these events on the conference presenters followed by a public lecture by Andrea Graziosi on “Stalin and Hunger as a Nation-destroying Tool.”

The conference succeeded in its objective of generating discussion on the similarities and the Communist leaders was dramatically different. Stalin was successful in his assault against the peasantry and consolidated his power. Mao was forced to retreat, and only after several years was he able to regain his stature. Kazakhstan’s great famine of 1931–33 also received considerable attention. The Kazakh famine claimed the lives between 1.15 to 1.5 million Kazakhs, approximately one third of their population. The famine was brought on by high livestock procurement quotas to feed Russian cities. This resulted in the elimination in a few short years of 90 percent of the livestock there. The campaign was accompanied by a project for the “total sedentarization” of the Kazakhs.

How these famines are remembered and commemorated generated consideration. In Ukraine the Holodomor is commemorated at the personal and civic level, although its memorialization has had inconsistent support from the state. In Russia the pan-Soviet famine is not a public issue. Kazakhstan went through a period in which its famine was the focus of attention, but the potential consequences of “politicizing” the issue have meant less attention. In China the famine came out into the open after Mao’s death, but it has not developed into a public concern. Rather, it has been “contained.” The question of imperialism emerged, particularly its applicability to the situation in the Soviet Union. Liudmyla Hrynevych noted that a future comparative examination of famine in the context of empires would have much merit.

HREC provided stipends to ten academics, including two from Ukraine, to support their attendance and held a special session to provide these scholars with the opportunity to interact with the expert presenters. Conference sessions are available at the Munk School and HREC websites (www.holodomor.ca). The conference was cosponsored by the Petro Jacyk Program for the Study of Ukraine at the Centre for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies (CERES) and the Asian Institute, both at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto. The Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre, St. Vladimir Institute, and the Canadian Foundation for Ukrainian Studies also provided support.

Presenters

-

Lucien Bianco

is an eminent French historian and Sinologist specializing in the history of the Chinese peasantry in the 20th century.

-

Sarah Cameron

is assistant professor of Soviet history at the University of Maryland-College Park. She earned her PhD in history at Yale University.

-

Andrea Graziosi

is a professor (on leave) at the Università di Napoli Federico II, an associate of the Centre d’études des mondes russe, caucasien et centre-européen (Paris) and a fellow of Harvard’s Ukrainian Research Institute and Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

-

Niccolò Pianciola

is Associate Professor of History, Lingnan University, Hong Kong. His research focused on the history of colonization and decolonization during the late Tsarist Empire and the early Soviet Union, and on the great famine in Kazakhstan.

-

Ralph A. Thaxton, Jr.

is Professor of Politics at Brandeis University. He specializes in comparative politics, including agrarian insurgencies and state-inflicted disasters in agrarian societies.

-

Nicolas Werth

is Research Director at the CNRS’s Institut d’Histoire du Temps Présent (Paris). Since his first book (Être communiste en URSS sous Staline, 1981), he has written numerous works on Soviet social history, Stalinism and mass violence.

-

Xun Zhou

is Lecturer of Modern History at University of Essex and the author of The Great Famine in China, 1958-1962: a Documentary History (2012).

-

Olga Andriewsky

is an Associate Professor in the Department of History, Trent University (Canada). The main focus of her research is 19th-early 20th c. history of Ukraine and the Russian Empire.

-

Kimberley Manning

is Associate Professor of Political Science at Concordia University.Co-editor of Eating Bitterness: New Perspectives on China’s Great Leap Forward and Famine (2011), she has published articles in Modern China, the China Quarterly, and The China Review.

Program

Videos

-

Communism and Hunger: The Soviet, Kazakh, Ukrainian and Chinese Famines in Comparative Perspective Holodomor Research and Education Consortium, CIUS, University of Alberta September 26–27, 2014 Day 2, Session 4, Round Table

-

Communism and Hunger: The Soviet, Kazakh, Ukrainian and Chinese Famines in Comparative Perspective Holodomor Research and Education Consortium, CIUS, University of Alberta September 26–27, 2014 Day 2, Public Lecture, Andrea Graziosi, Stalin and Hunger as a Nation-Destroying Tool

Photos

Sponsors

Petro Jacyk Program for the Study of Ukraine (Centre for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, University of Toronto)

Asian Institute (Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto)

Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre

St. Vladimir Institute

Canadian Foundation for Ukrainian Studies

Holodomor Research and Education Consortium (Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta)