Diaspora Responses

Research continues to produce new insights on the activities of the Ukrainian diaspora worldwide in the 1930s to raise awareness of the Holodomor.

The Ukrainian Famine of 1932-33 came to the attention of a wider scholarly community and public in the 1980s during the commemorations of its 50th anniversary. Much of the discussion at this time was associated with the reasons for the Ukrainian community’s attention or even fixation on this event, which was at the time denied by the Soviet Union. Some commentators saw its depiction as a man-made famine and as a genocidal act as a way to win victim status for Ukrainians and believed the large numbers of victims claimed as even an attempt to equate it with the Holocaust. Some saw it as propaganda of emigres in the Cold War. As research on the Holodomor has expanded, the degree to which Ukrainians in the 1930s in Western Ukraine, in the European centres of the Ukrainian emigration, and in the Ukrainian diaspora communities in North and South America saw it as a genocidal act has become apparent. Thus long before the term genocide was coined or given a legal status, the genocide thesis for the Ukrainian Famine had emerged. In the same way, before the Holocaust, figures of 6 or more million victims were quoted. The text reproduced below was an example of the attempts of members of the Ukrainian diaspora community to convince Western societies and leaders of the criminal nature of the Soviet regime. Published on July 19, 1935, under the subheading “Soviet Russia’s Crime against the Ukraine,” it illustrates how the Famine had become a central topic for anti-Soviet Ukrainians in the United States. The author like the overwhelming majority of the Ukrainian American community originated in Western Ukraine, but already saw the Famine as a planned anti-Ukrainian action that should concern all Ukrainians and a wider public.

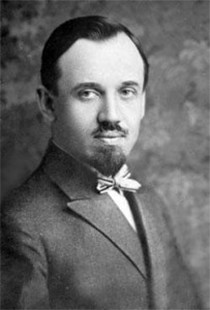

Lesio Sysyn (1895-1987) was born in the village of Mshanets in the Staryi Sambir County of Habsburg Galicia. The village pastor Father Mykhailo Zubrytsky had a great influence in instilling a love of learning and Ukrainian patriotism in him. In 1913 he left Galicia for the United States and ultimately settled in Garfield, New Jersey. In the 1920s he led the movement to form Holy Ascension Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Passaic, New Jersey. He remained dedicated to the cause of Ukrainian independence throughout his long life and was a supporter of the Organization for the Rebirth of Ukraine. He was a frequent contributor to the Ukrainian American press, with numerous articles on community and political issues published in Svoboda. In the 1940s he assisted in establishing the branch of the Ukrainian Congress Committee in Passaic. He maintained a life-long dedication to informing the world community about the Famine. A frequent speaker at community events, he introduced the memorial commemoration in Passaic on the 30th anniversary of the Great Famine on December 1, 1963 (See the Memorialization section on St. Andrew’s Memorial Church in South Bound Brook, excepts from Ukraïns’ke pravoslavne slovo February 1964, vol.15, no.2). He took great pride in the building of the new Holy Ascension church in Clifton, constructed by the well-known architect Jaroslav Sichynsky (https://ukrcoc.org/en/about-us). He kept a lively interest in contemporary Ukraine, condemning those who wanted to come to an accommodation with Soviet Ukraine (Novyi shliakh 6:1966,15) and supporting the work of Smoloskyp. He was present to speak at the 60th anniversary of his parish in 1985 and to call its members to remain loyal to its Ukrainian identity, but he did not live to see Ukraine’s independence.

Lesio Sysyn’s publication of an expansive discussion on Ukraine in a major New Jersey newspaper was seen as a success by the community and ensured its reprinting in the New Jersey Ukrainian daily Svoboda. His writings demonstrate that he followed events in Ukraine closely. Still the detailed discussion of events in Soviet Ukraine and in the Western press in the text and the level of its English raise the possibility that this may have been a text prepared by one of the Ukrainian political factions and distributed to its members. One would have to find other copies of this text to prove such a hypothesis. In any event, the author had succeeded in reaching one public, albeit in a regional newspaper in an area with large Eastern European immigrant communities.

Vladimir Kaye-Kysilewskyj was a major figure in the pre-history of Canadian multiculturalism in the 1950s and 1960s. After emigrating to Canada in 1925, he became editor of the newspapers Zakhidni visty in Edmonton (1928–30) and Ukraïna in Chicago (1931). In the 1930s he was an active lobbyist for Ukrainian causes in London, England, serving as director of the Ukrainian Bureau there in the period 1931–39. In fulfilling his mission to inform Western opinion about major issues affecting Ukraine, Kaye-Kysilewskyj developed a working relationship and friendship with the journalist and personal secretary of David Lloyd-George, Gareth Jones. Their contacts, which began before Jones visited Ukraine during the Holodomor, are reflected in Kaye-Kysilewskyj ’s diary. The pages where Jones is mentioned are included here. The diary will be published in the series “Ukraine-Europe, 1921-1939” of the Petro Jacyk Program for Study of Modern Ukrainian History and Society of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. Professor Alexandra Hnatiuk is editing the diaries and writing an introduction to their publication.

Mentions of Gareth Jones in the diary of V. Kaye-Kysilewskyj

Vladimir-Kaye-Kysilewskyj: in Europe, Canada, and Britain

Article by Thomas M. Prymak, courtesy of the author

Dnipro (Chicago, Philadelphia, Trenton, NJ; 1921-1926, 1928-1950) was a Ukrainian-language newspaper of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the United States. In the period 1931-40 it was published in Philadelphia as a biweekly. Its intended primary audience was the Ukrainian immigrant community in the US, and the range of topics covered included news from Ukraine, faith, church and community events and affairs, literature, and letters from readers.

The following selection of excerpts from Dnipro gives some sense of what Ukrainians abroad knew about the 1932-33 famine in Ukraine at the time and about the larger socio-political context in which it occurred. In 1933, virtually every issue included more than one mention of the famine as well as related stories about Soviet economic and demographic policies, political purges, the war on religion and church, reversal of the Ukrainianization policy, and escapes from the Soviet Union.

Ukrains’kyi Holos was a diaspora newspaper serving the Ukrainian-Canadian community, and was first published in 1910 in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Listed below are issues from 1934 and 1935 that feature information and photographs related to the Holodomor. Though the photographs are not attributed in the paper, they are now known to have been taken by the Austrian engineer Alexander Wienerberger and smuggled out of the Soviet Union. The materials shed light on the degree to which the Famine was an issue of importance among the Ukrainian diaspora already in the 1930s.

Olgerd Bochkovsky (1885–1939) was a Ukrainian sociologist and leader in the Ukrainian community in Czechoslovakia who headed a committee formed by émigrés to secure aid for the starving during the Famine in Ukraine of 1932-33.

Reproduced here are five texts by or about Olgerd Bochkovsky, from the publications Olgerd Ipolyt Bochkovsky: Vybrani pratsi ta dokumenty, Tom 1 (Kyiv: Ukraina Moderna and Dukh i Litera, 2018) and Olgerd Ipolyt Bochkovsky: Vybrani pratsi ta dokumenty, Tom 3 (Kyiv: Ukraina Moderna and Dukh i Litera, 2019).

These and other Bochkovsky volumes are available for purchase at CIUS Press.

Born in south-central Ukraine to a family with Polish and Lithuanian roots, Bochkovsky was a good student and became proficient in many languages. He began his postsecondary studies in St. Petersburg, Russia, and after the Revolution of 1905, completed a degree in philosophy at Charles University in 1909. A frequent contributor to the Ukrainian and Czech press on nationalities issues, Bochkovsky became a member of the diplomatic mission of the Ukrainian People’s Republic to Czechoslovakia in 1918. From 1922 to 1935 he taught at the Ukrainian Husbandry Academy in Poděbrady and later worked at the Ukrainian Technical and Husbandry Institute in Prague.

In mid-1933, Bochkovsky became the head of a famine committee in Czechoslovakia dedicated to helping the starving in Ukraine. Not long after, Édouard Herriot, the three-time French prime minister and long-time mayor of Lyon, went on a high-profile tour of the USSR at the invitation of Soviet authorities. The French politician’s first stop was in Ukraine, where he attended official, stage-managed meetings and was taken to view Potemkin-style villages. While in Kyiv and in Kharkiv, Herriot praised conditions in the Soviet Union, making no reference to famine.

In response, Bochkovsky sent an open letter to Herriot’s mailing address in Lyon that respectfully suggested that Herriot had “fatally erred” in his assessment of Soviet social development and had failed to see “the horror of the current state of Ukraine.” Herriot continued to lavish praise on the Soviet Union upon his return to France, going so far as to claim that the campaign around “la pretendue famine de la Ukraine” had been orchestrated by Berlin and calling those raising the alarm bells nothing more than agents of or sell-outs to Hitler. Bochkovsky, a dedicated social democrat, believed that people concerned about the assault on European values represented by Nazi Germany should also be critical of the USSR. He penned a response stating he had misjudged Herriot’s earlier comments about the Soviet Union as the polite and politic reaction of a visitor and suggested that the former prime minister had moved from being a Sovietophile to maniacal in his support of the USSR. Bochkovsky wrote in conclusion that he found it pointless to engage in polemics with people who resort to shameful insinuation and suggested that their words should be noted down for eternal public disgrace.

Olgerd Ipolyt Bochkovskyi – Holod na Ukraini

Article by Bochkovsky of 1934 on the Holodomor. This article was published for the first time in this volume.

Robota u Holodovomu komiteti (‘The Work of the Holodomor Committee’)

Section from the introductory biographical essay "Olgerd Ipolyt Bochkovskyi-narys biohrafii”by Iryna Kanevska, describing Bochkovsky’s activities as a member of a committee in Czechoslovakia dedicated to helping those suffering during the Famine

Olgerd Ipolyt Bochkovskyi: ‘J’accuse!’ [‘Ia zvynovachuiu’]

Article by Olia (Ola) Hnatiuk and Myroslav Chekh (Mirosław Czech) examining Bochkovsky’s Open Letter to Herriot and follow-up article in the context of the silence of European powers who were well aware of the Famine.

Do p. Eduarda Herriot – Otvertyi lyst prof. O. I. Bochkovskoho (‘To Édouard Herriot – An Open Letter from Olgerd Ipolyt Bochkovskyi’)

Ukrainian version of the Open Letter by Bochkovsky sent in French to Édouard Herriot (former French prime minister) at the time of Herriot’s trip to Ukraine in which Bochkovsky asserts that Herriot had seriously erred in positively assessing the situation in Ukraine. The letter later appeared in Ukrainian on 9 September 1933 in the Lviv newspaper Dilo and not long thereafter in the Lviv edition of the Paris newspaper Tryzub as well as the Ukrainian-American newspaper Svoboda. The original also appeared in several French and Belgian publications.

Pan Errio – Sovity ta holod na Ukraini (‘Mr. Herriot – Soviets and Famine in Ukraine’)

Article by Bochkovsky taking former French prime minister Herriot to task for his continued support of the Soviet Union and for his attacks on those who spoke out about the Famine. It appeared in two installments in the Lviv newspaper Dilo (12 and 13 December 1933)